Great Grandmother

My great grandmother was wasteless. She would use anything up until finally it was a husk and even then she would stuff the crumpled paper inside the empty can into the orange juice carton with the eggshells. She had to wear it out. She would put sequins on rags and make doll clothes and when they were rags again she would clean. She was thorough. She collected stamps, one-cent stamps that reminded her that if the Great Depression could happen once it could happen again so she collected coins too and gave knitted things at Christmas.

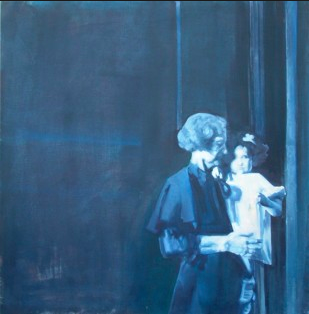

Like her trash she was compacted. She hunched down and in and her skin rose and fell in tiny rice paper folds and her fingers bent towards each other and one could imagine she was a weathered tree wrapping its roots around something precious and hidden. She was transparent and flawless and the white white of her body was shocking. There was no grey. No age spots. No freckles or scars or redness or errors. Just a crystal clear bonnet of white hair atop skin that had defied age and been crushed in its wake.

She played cards. She made crocheted blankets and socks and time for babies born too early, too weak, too light to take home, compromised lives caught at the starting line as she approached it from behind. They were handheld and bottle-fed and looked astonishingly like herself. She liked certain. She liked things she could get her hands around, things that were measurable and firm. She liked small things, collectibles, things that could be guaranteed to keep on coming but never different enough to warrant surprise. Her hair never changed, or her dolls or her car or the television shows leading into her nightly routine. My grandmother was born and raised. My mother followed. I came along, my cousins and sister. Through it all she was the same shrinking woman who worried about details and could take or leave a big picture. She kept tally of her children and grandchildren and great grandchildren and it seems as if her blood thinned and spread out until finally it flowed and she was left dry and breathless.

I imagine she felt powerful before she died. In all of the empty time she spent sitting between a lawn chair or a swinging bench or on sunken living room furniture as her bones collapsed under their own weight and her yarn frayed and the TV spit back reruns she must have grasped the mark she’d had on the world. She must have sensed the impact of her three children and eleven grandchildren and sixteen great grandchildren and all the lives they led and in turn affected. I remember sitting at the kitchen table with her as four generations held dog-eared and spaghetti-stained cards and we all took turns trumping one another and toddlers squealed and men debated and women slipped away and she stared straight through my hand with those muted blue eyes that we’d all taken from her and I was aware of one life’s weight and I imagine she was aware of the generations still inside of me.